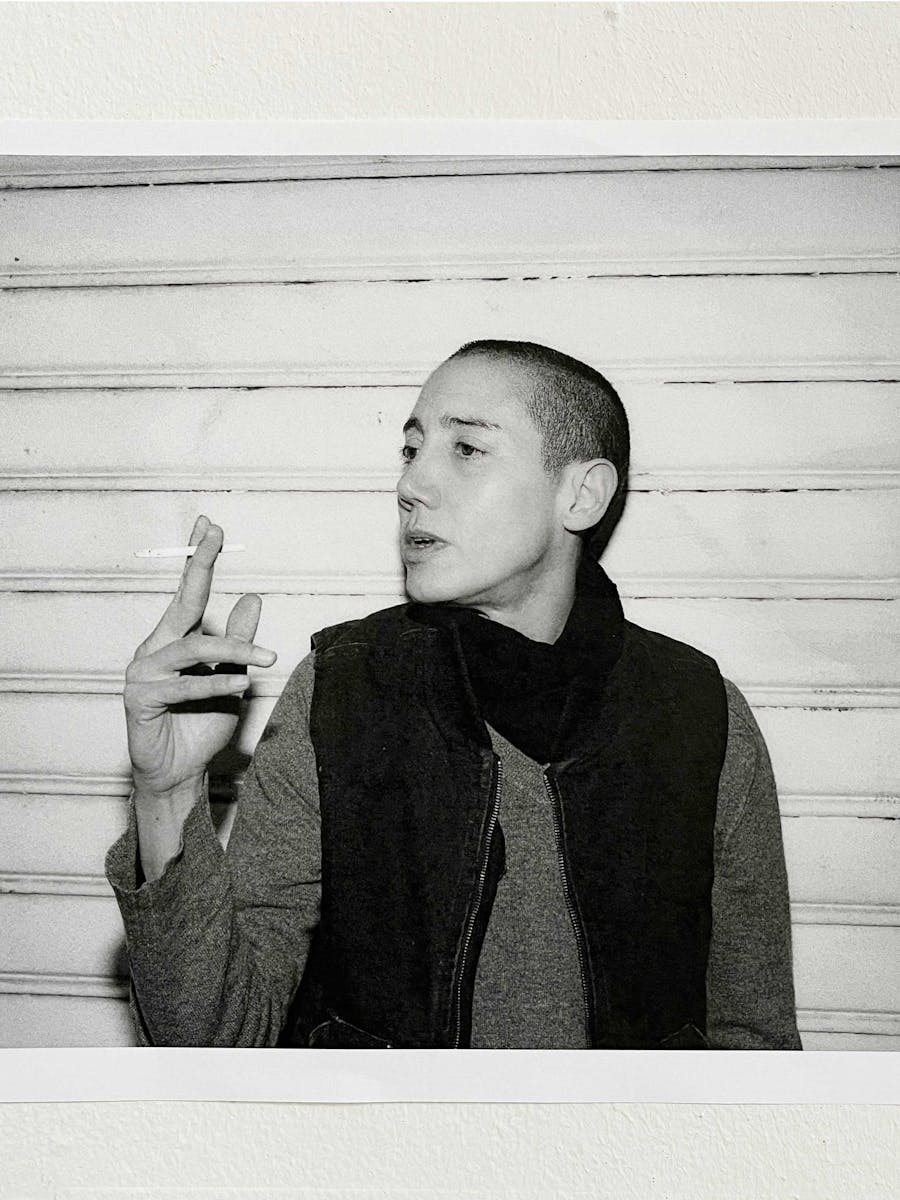

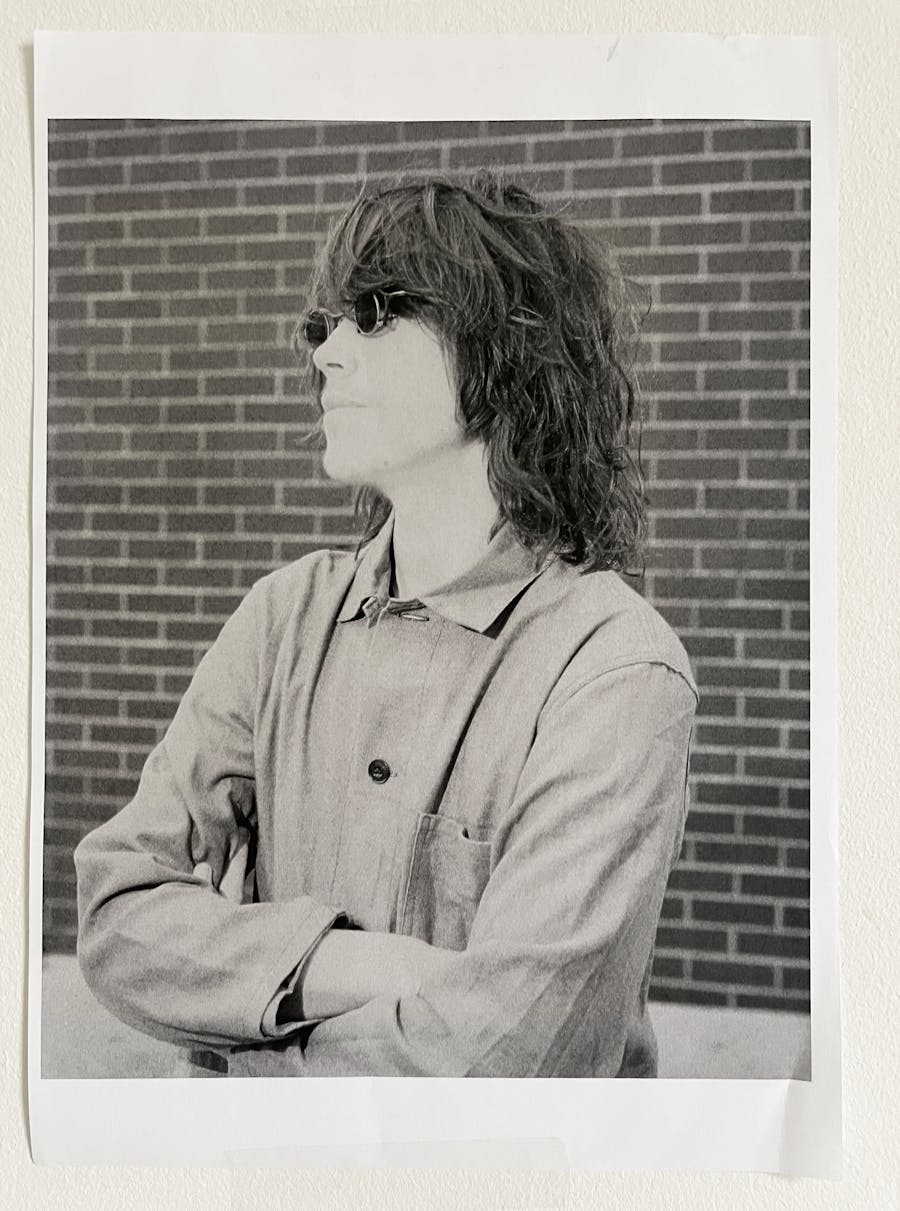

Tiago Rodrigues – the Portuguese actor, director and dramaturge, who since 2014 has helmed one of the most prestigious cultural institutions in his country, the Dona Maria II National Theatre in Lisbon – is a major figure in contemporary European theatre, whose multilingual plays have been widely performed, not least at the Avignon Festival. An energetic and passionate man in his early 40s, bristling with ideas, he has reinvented a theatre of meaning and emotion which forges an idea of a world in of perpetual questioning.

One of your most recent plays performed in France, The Way She Dies, operates as a deconstruction and reconstruction of the story of Anne Karenina by Tolstoy; you did something similar for Madame Bovary with the play Bovary, based on the real trial of Flaubert in 1857… Rewriting, using different languages, working collectively: is it thus that you approach your metier as a dramaturge and director?

⏤ My relationship with writing and directing is sustained by my work as an actor, which involves knowing how to translate an existing work into another language, that of the stage. I have really come to understand the importance of taking liberties as a ‘translator for the stage’. The play Bovary is a good example: on the one hand, it is a version of Flaubert’s novel, and on the other, there is the literary phenomenon, the effect of the novel. By going back to Flaubert’s trial for indecency, we wanted to show what that novel brings to us in the present day. The deconstruction was not intended to deconstruct the work, but was rather an exercise in translating it into our historical moment, our geography and our experience as a group of artists. We want to share with the public our love for the work but also to appropriate it for ourselves.

With your theatre, you appeal directly to the present, to the instantaneousness of the live spectacle, but how, in fabricating this art, do you deconstruct it, and through that very act bring it bursting to life?

⏤ It’s a consequence of the way I work : life lived around the creation of a play percolates into the play. When I adapt or when I write, I’m thinking more about the relationship an actor will have with the idea of a character or a scene than the scene itself. I am much more interested in the effect procured by a scene which evolves the identities of the actors themselves, not just the tools of their trade but also their personality, their lived experience, their emotion at the moment they are discovering and reading the text. For me, plays are a portrait of time lived together.

You don’t hesitate to change the text during performances even if it has already been published…For example, the play text of Bovary, performed again by French actors at the Théâtre de la Bastille in Paris in 2016, after its run in Portugal.

⏤ The play texts always emerge from debates, discussions… For that play, we wrote a new version of the text which had already been published since the actors changed and the mise en scène had to be different because it’s always the result of an encounter. The text must be receptive to the needs of actors and the challenges I give them. They are like letters – I write in the morning what will be performed in the afternoon – written to actors and which demand a response. I am not really bothered about posterity or the perdurability of my texts, which don’t have a sacred nature at all ; I am much more interested in the act of creation, the moment of the performance itself ; as a result, there are several versions of the same text published in Portuguese and French.

And I never have the right version on me when I need it… For the play based on Anna Karenina, The Way She Dies, translation as such was always at the heart of our rehearsals since the four actors spoke different mother tongues – Dutch and Portuguese – and French was used at several points. We wanted to make that effort palpable in the writing of the play. It was a wonderful opportunity to make explicit to the public something which is always implicit in my plays: the fact that there is always a translation game, a manipulation of sounds, words, that the actor is in the process of putting in place to arrive at meaning.

Changing scenery and costumes in front of the audience, actors addressing the spectators directly… The fabrication of the theatrical material is always occurring before our very ideas, as it is in the play Sopro, which sheds light on a métier which is normally in the shadows, that of the prompt. Is it important to you that theatre shows what happens behind the scenes ?

⏤ Yes, I think that it is important to see the strings. We all know that theatre creates an effect, I want to show the beauty behind the invention of that effect. I am not anti-illusion, but I prefer it to be a virtual contract with the audience. At the start of most of my plays, nothing much happens and gradually, a kind of code starts to click into place. The actors, little by little, present the rules of the game, like children who spend an hour preparing the game and only 5 minutes playing it. That’s what Sopro is about: the whole play is really the seven lines of Racine declaimed by the prompt right at the end, and the two hours before set up the rules of the game, so that those lines can mean something. And then, I’m also fascinated by that simpler way of imagining the stage and above all of seeing what is spectacular in a movement of the finger or an actor’s wrinkles, more than in fireworks…

You are fascinated by stories and above all the great myths : Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary, Antony and Cleopatra. Do you use these great enduring figures to examine the present moment?

⏤ What interests me in these great stories is not what is going to happen, which we know already, but how it would happen today. What are the details this time round? This is what is said in Anouilh’s Antigone, that with tragedy you can relax – because you know something bad is going to happen – and take in all the details of the story. With the troop of The Way She Dies, it was by starting to talk about Tolstoy’s character or Madame Bovary that we became aware of the power of reading: literature can change lives, privately or collectively. Then we decided to work on the fact of reading Anna Karenina, trying to recount what it is like to live with literary ghosts: to bring to the stage people who have been affected, infected by these words, by the spirit of the character and of Tolstoy at different times.

The power of words is at the root of your vocation: how can they transform the world and how can you conjure with them so that they become a form of action?

⏤ For me words contain more images than images. What I have always loved about theatre is its power to evoke. I love that border where you show some things by evoking others. This border between words and action really interests me because I think that theatre takes place in the anteroom of action, the anteroom of life. It is part of the architecture of life, it is not adjacent to the world or to life, but, at the same time, it lives in a territory with other, mysterious rules. There is a suspension of everyday rules which allows us to go to a strange land whilst remaining in our own country. And that theatrical border is simultaneously a space of fiction and a human gathering where new ideas surge forth and lead us to action. Theatre is not going to change the world, but there is this idea that in a theatre, there is a potential for danger because of the physical presence of the audience, and that cannot be denied. That’s why I prefer to stage and see plays where we don’t pretend to have a fourth wall. For it is in accepting that we are all in the same room without pretending, in a space where there are still rules to be invented, that there is the possibility of collective transformation. Ephemeral perhaps, and slight, but together thousands of these almost nothings can add up to something.

Your next piece, Catarina and the Beauty of Killing Fascists, will resonate with the rising threat of fascism in Europe.

⏤ The premier will take place in May 2020 in Lisbon and I will write the play during rehearsals. It is the story of a family with the habit of killing fascists, but an internecine conflict erupts when a young woman of 20 is unable to honour the tradition. The question of betrayal arises in the heart of the family: is she a pacifist or does she lack courage ? It is of course a reflexion on the rise of new fascist movements in Europe, but it is also an interrogation of the everyday reactions to this climate within a personal and family context. This performance is all there to animate language. In the title, the use of the word ‘fascist’ has already upset a lot of people but I think it is important to reclaim words rather than fall into the kind of euphemisms which normalize things ; « killing » raises the question of violence and terrorism, « the beauty of killing » is a paradox but one which has fuelled centuries of war and « Catarina » is the name of a Portuguese martyr murdered by fascists in 1954.

Did you feel a sense of personal or political urgency in deciding to tackle this subject and write this play?

⏤ These are questions which begin to bubble up as I observe the world. This upside-down world—in the play, killing is normal whereas to be a pacifist is shocking —, we see it in our society. Greta Thunberg is insulted by the right and left, but also by intellectuals. What shocks me is that the elite spend their precious time attacking a young girl who puts forward claims that are well established and cannot be gainsaid. It’s complete fiction ! By the same token, what we are all – including our governments – doing to migrants, seems to me to belong to the order of horror, to be a crime against humanity. The question I ask myself today is therefore: how to live in a present where all that is happening and I am making theatre. I ask myself if thought is enough today in a world where communication is so controlled by fake news, and if language still has a value, and if so, what ? I also think about resistance, because after all we are living in a Europe where Edgar Morin is still alive. I wonder if we can trust in democratic norms. The play is animated by several of these questions. When I think about the character of Catarina, I see someone who is calling into question what we think of as normal today.

Translated into English by Sara & Emma Bielecki.

Antoine et Cléopâtre, 2015

Bovary, 2016

Sopro, 2017

The Way She Dies, 2017

Catarina ou la beauté de tuer des fascistes, 2020

His plays are available in French translation through Les Solitaires Intempestifs.