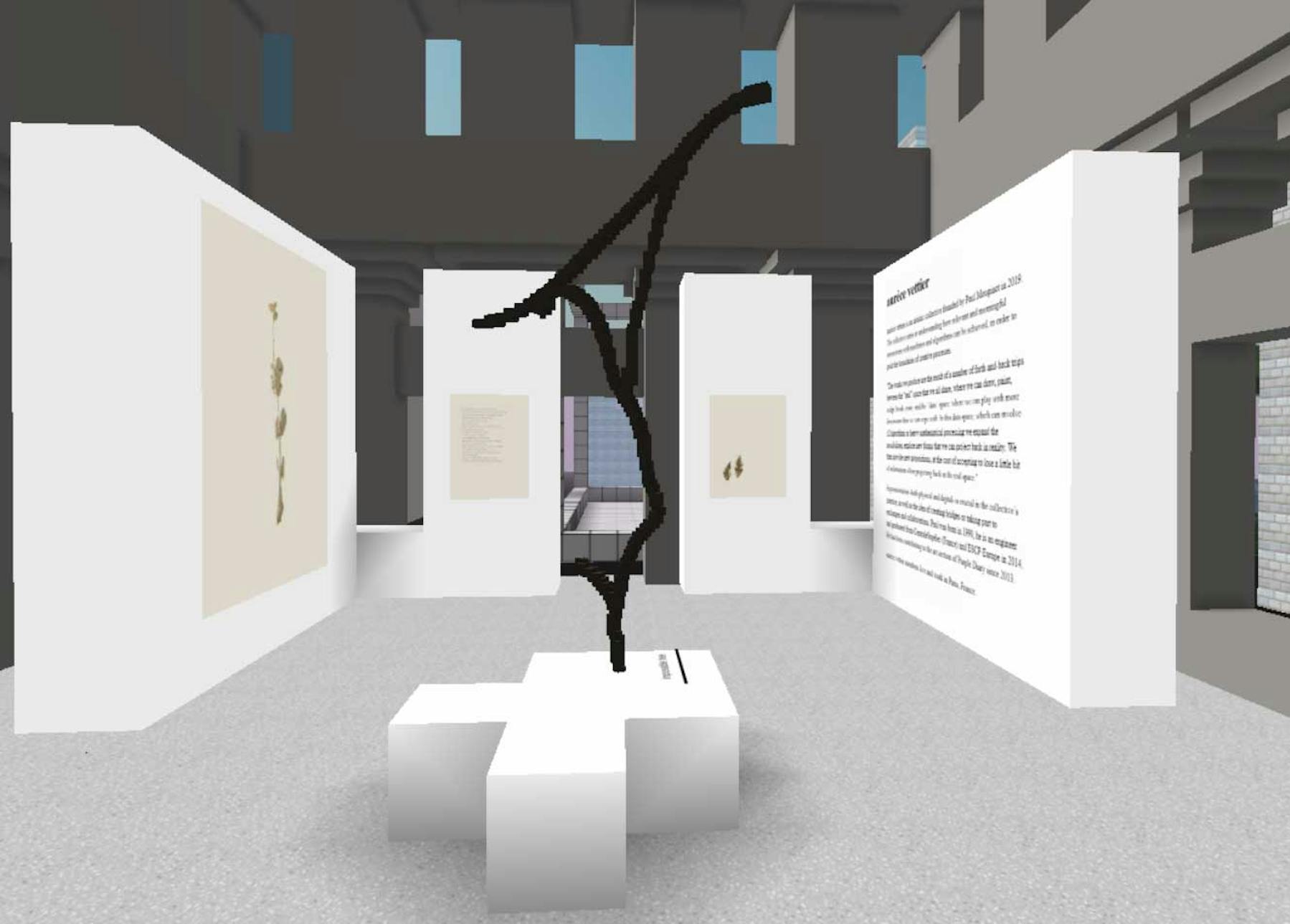

There are brilliant minds, capable of juggling science and art, the real and the imaginary. Paul Mouginot, specialist in artificial intelligence and founder of the art studio aurèce vettier, is one of them. In 2020, he shared with Exhibition Magazine a series of hitherto unpublished poems written by a text generation programme using Markov chains, an algorithm well known in mathematics, as well as a herbarium of the future, a bouquet of photographs of flowers and vegetables – all of them also ‘algorithmed '. In April 2021, the artist-scientist organized, along with bem.builders (an agency who specialize in the metaverse) and Exhibition Magazine, an art exhibition in Cryptovoxels, housed in a purpose-built pavillion, both brutalist and florentine. In a poetic text, Paul Mouginot describes the parallel worlds of the metaverse, between reality and simulation, raw voxels and ones processed by the imagination.

In his short story ‘Circular Ruins’, Jorge Luis Borges imagines a man emerging from ‘unanimous night’ and settling in the ruins of an ancient temple, with a goal both simple and supernatural : he wants to dream up a human being in the most granular detail – its cells, limbs, organs, face – and give it life, project it into reality. His task complete, he discovers in the final moments ‘[w]ith relief, with humiliation, with terror [...] that he also was an illusion, that someone else was dreaming him’.

Simulating the world

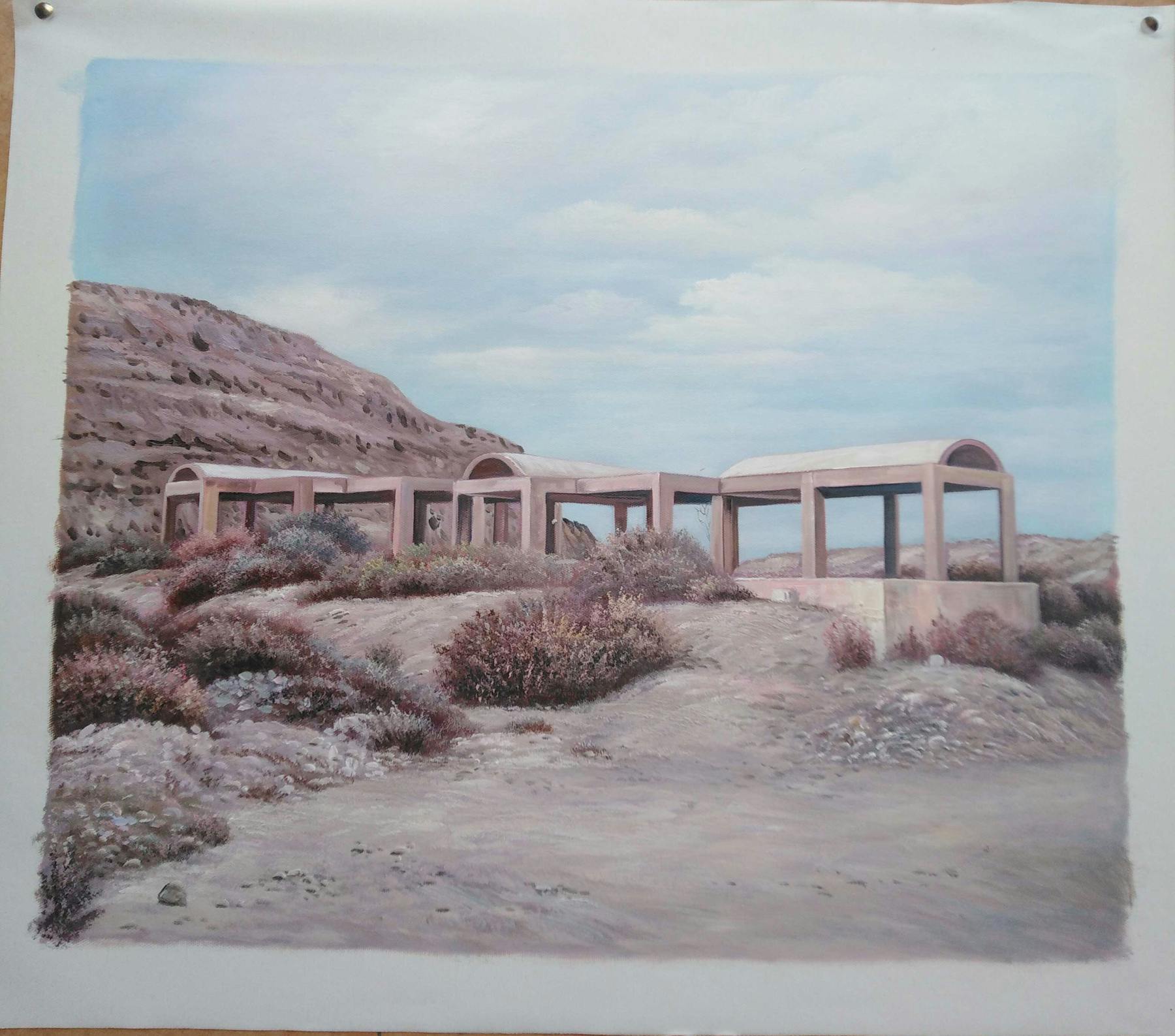

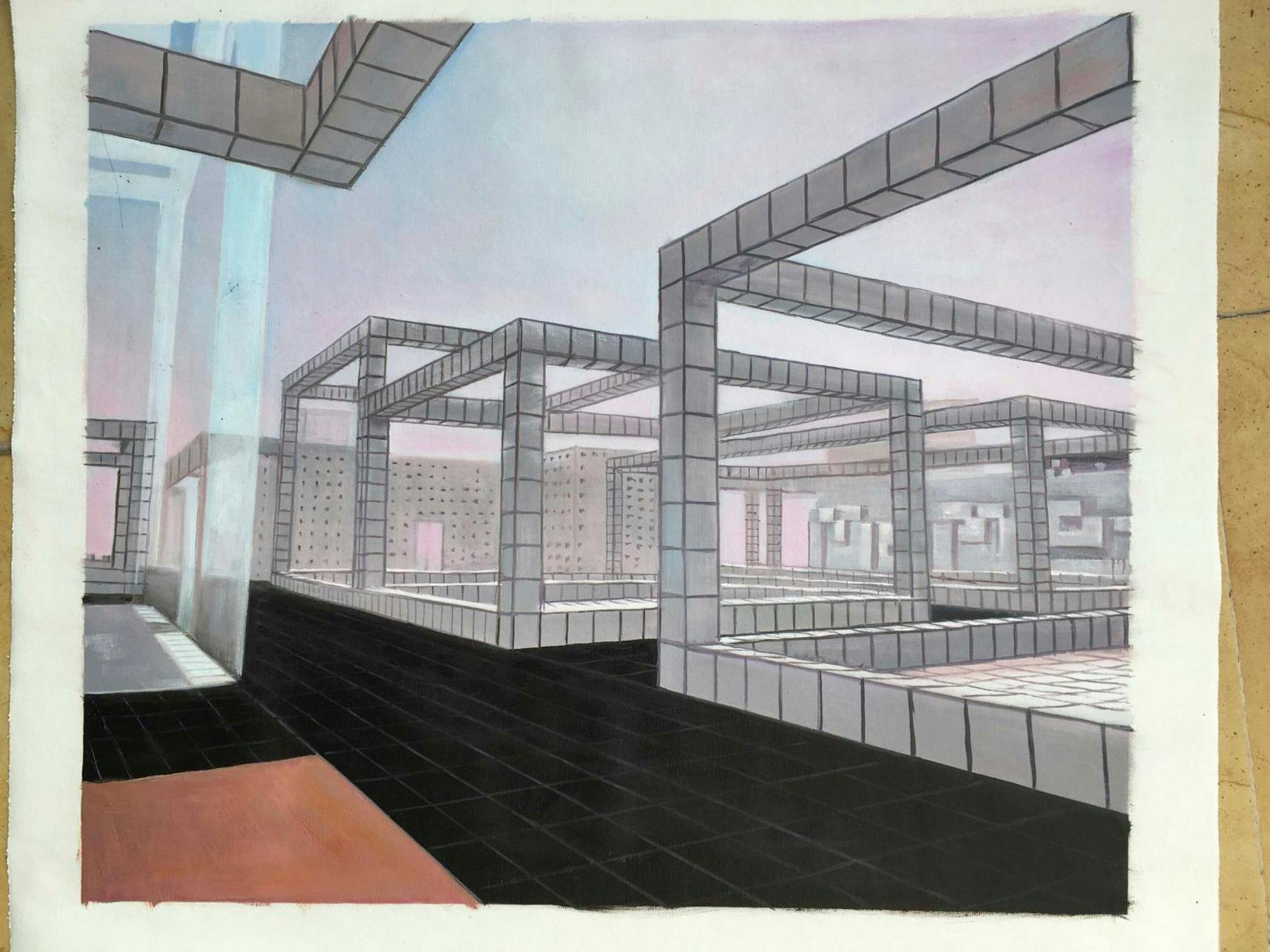

At the start of 2021, creative experiments between Exhibition Magazine and bem.builders, an agency who specialize in the metaverse, gave rise to what was probably the first metaverse building run by a magazine in Cryptovoxels : an art foundation drawing inspiration from both florentine and brutalist architecture, housing an exhibition of photographs by Boris Ovini and the art studio aurèce vettier.

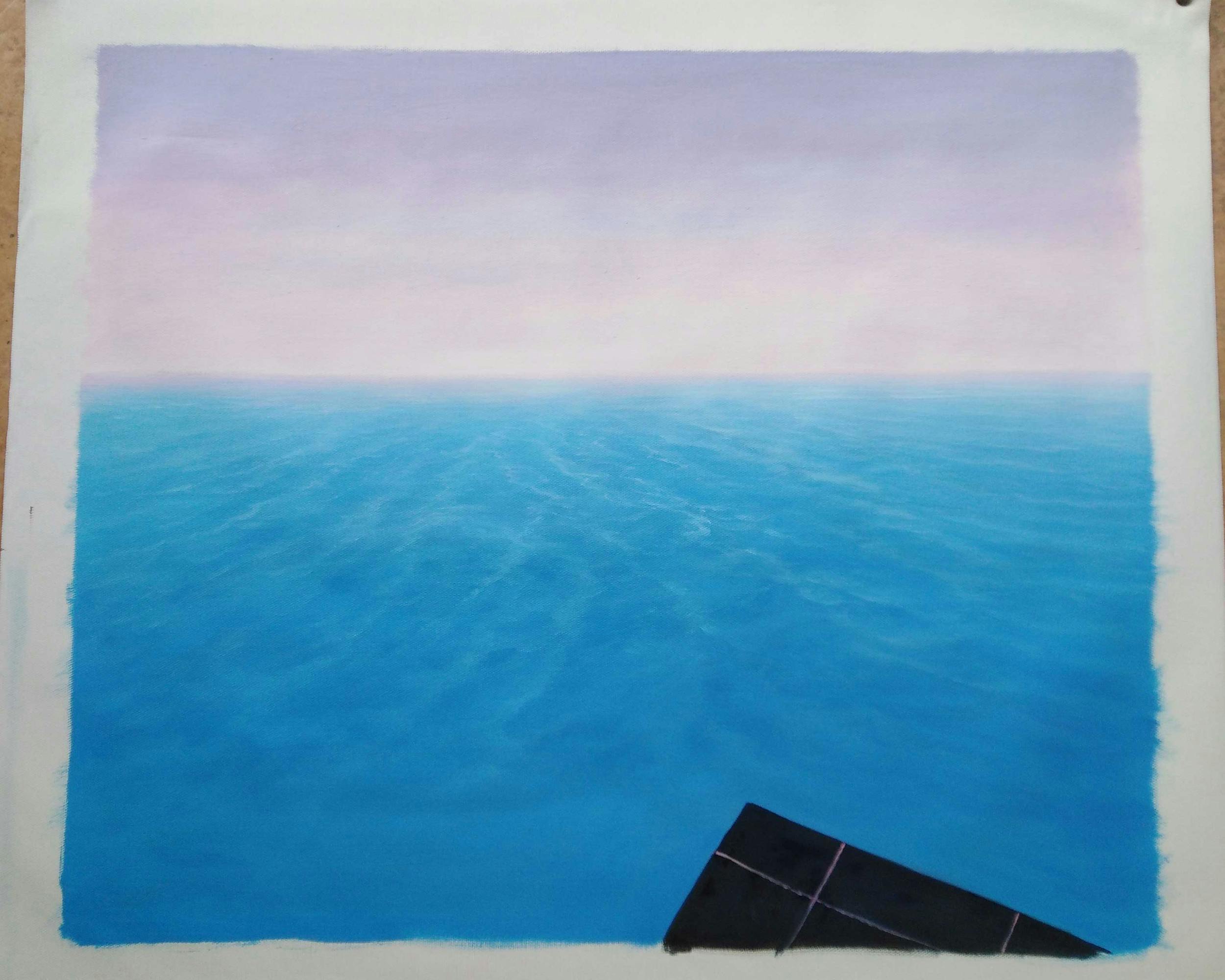

Around that time, wandering through the metaverse, we met Ricky, a virtual landowner who graciously allowed us to build on one of his plots, in the district called ‘Milan’. This neighbourhood was still under-developed and you could see the edge of the map, where the violet sky met the sea. Anonymous avatars appeared and disappeared a few seconds later, and when we managed to exchange a few words with them, almost all of them said they were looking for a place to build an art foundation, an exhibition space or even a mausoleum. Sometimes, upon entering a building that already been constructed, we would find ourselves in a club where other avatars, wearing virtual clothes, danced around a silent DJ.

During these strolls in the metaverse there was always a feeling of melancholy and immense loneliness. However, in every complete building, in every initiative, you could feel the desire to leave a trace, something which can survive us in the blockchain. This dream recalls the final sentences written by Perec in Species of Spaces (2) : ‘I would like there to exist places that are stable, unmoving, intangible, untouched and almost untouchable, unchanging, deep-rooted; places that might be points of reference, of departure, of origin: my birth place, the cradle of my family, the house where I may have been born, the tree I may have seen grow (that my father may have planted the day I was born), the attic of my childhood filled with intact memories… Such places don’t exist, and it’s because they don’t exist that space becomes a question, ceases to be self-evident, ceases to be incorporated, ceases to be appropriated. Space is a doubt.’

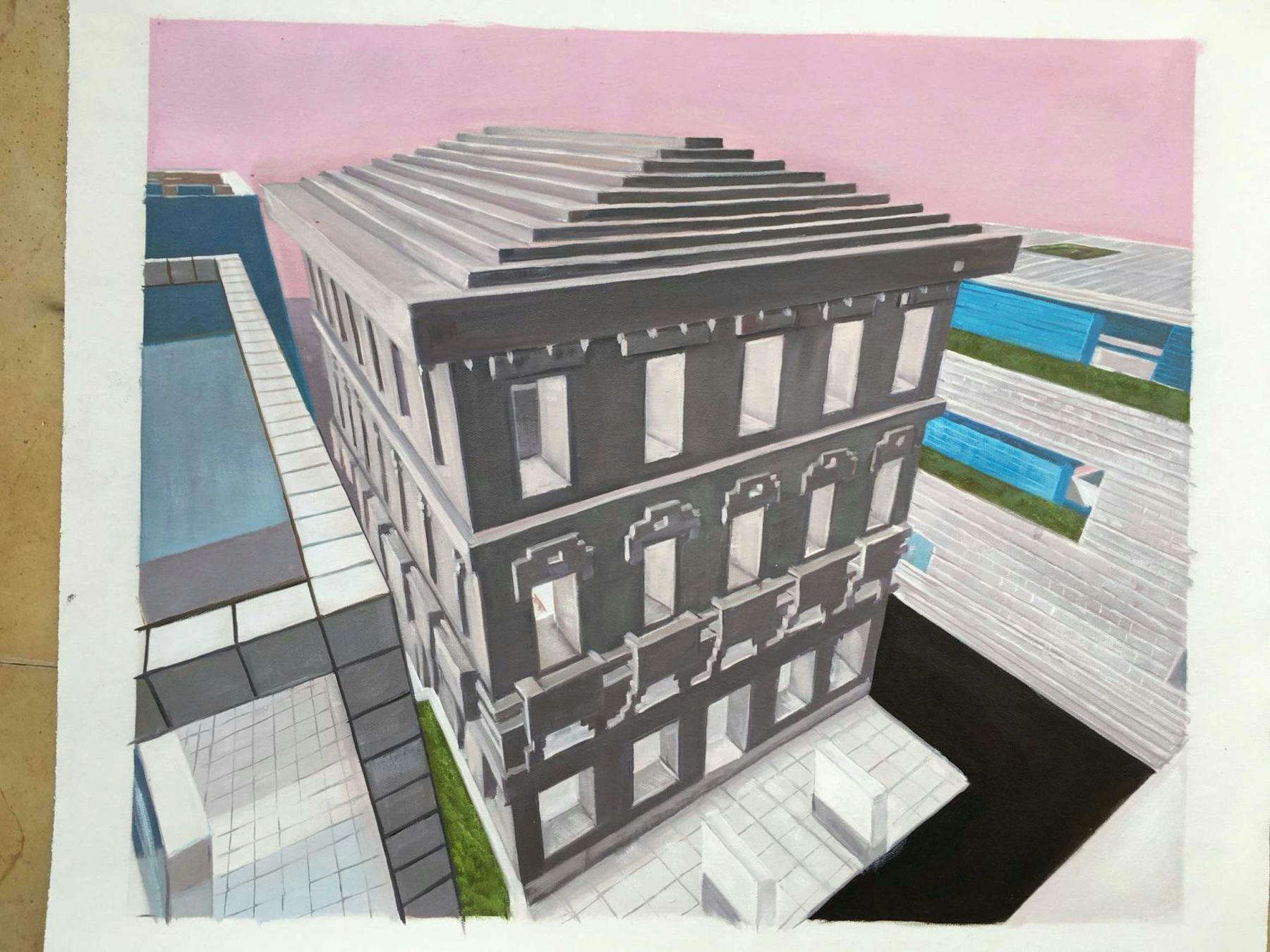

Returning to these places, a year after the construction of the building in Cryptovoxels, it is noticeable that the neighbourhood has gentrified considerably: one’s gaze is drawn to cute galleries of voxellised masks and large constructions housing the pricey NFTs of crypto-rich collectors.

So, if these ideal, immutable places do not exist, are we dreaming them up here in the metaverse ? And to what end ?

The first attempts have been, it must be said, visually unconvincing. Cyrptovoxels Decentraland, The Sandbox and Somnium Space, are, despite their graphic interest, extremely far from a faithful representation of the real, which in any case is not the goal of their respective creators. It’s a ‘voxellised’ aesthetic, in other words an environment reconstituted by the little 3D pixels called ‘voxels’.

In April 2021, however, the giant NVIDIA Omniverse announced that it wanted to create a particular kind of metaverse which would be a virtual twin of our world. This is obviously a long-term objective, but one that is nevertheless credible – even achievable – on the part of the global leader in computer graphics. The idea is that each town, each factory, each building can have a digital twin, a perfect simulation of its real version, with the possibility of including tests with a physical dimension. In a factory, the briefest interruption to a production line’s operation is costly, soit’s not hard to see the benefit of simulating settings in detail before making changes.

Numerous projects in the metaverse are starting to emerge, banking on visual realism. If it is a question of best representing our world in a digital space, the last words of the Borges short story invite us to invert the terms of the question : is our old world not itself a simulation?

The physical world : a ‘simulated reality’ ?

The more time we spend in the metaverse, the harder it is to prevent our minds wandering freely around the perennial question of simulation : is our physical world, and our life in this world, itself the product of a simulation ?

In 2003, the philosopher Nick Bostrom published an article called, ‘Are you living in a computer simulation?’ (3), taking up once more a question asked by Plato, Locke and Berkeley. According to Bostrom, and working on the assumption that the computing power available to future civilisations is enormous, there is a high probability that one of the three following propositions is true :

1. The human species is very likely to go extinct before reaching a ‘posthuman’ stage;

2. Any posthuman civilisation is extremely unlikely to run a significant number of simulations of their evolutionary history (or variations thereof);

3. We are almost certainly living in a computer simulation.

These dizzying propositions had been put forward by many illustrious predecessors of Bostrom, notably Berkeley and Locke. For Berkeley, especially, everything is perception: ‘colours, ideas, forms, movements, tastes, smells only exist through the prism of our perception.’

So, are we living in a ‘simulated reality’ ? I am thinking about my cat, who only knows three universes : my house, that of my parents, and the vet’s surgery. Ah ! If only he knew that there was more, that the universe is infinite and perpetually, speedily expanding.

In mathematics, especially in algebra, it is possible to work with a high level of abstraction, in spaces which blithely supersede the three dimensions. This enables us to perform operations that are impossible in our classical mental conception. By accepting the loss of some information, we can come back down to lower dimensional space, which is more comprehensible.

And what about us ? Where are we in all this ? Are we prisoners of Plato’s famous cave, where we are prisoners, and puppeteers project shadows on the wall ? We think we see reality, but we are only really seeing its projection.

Hoping the soul survives

It is not necessary to be a philosopher or an epistemologist to give one self up to a deeper reverie, that of the third scenario proposed by Bostrom : if we are, in fact, part of a virtual reality, what are the implications ? Above all, the question is, are we the end product of a hierarchical imbrication of virtual realities, nestled one inside another, like a set of Russian dolls ?

The theoretical physicist Sean Carroll studied this idea some years ago. He hypothesized that if a simulation of a world were capable of launching its own simulation, then there would be a loss of com - puting capacity, and therefore of the possibilities available, at every new ‘sub-level’. As a result, we would currently be in the lowest level simulation, the ‘lowest level of reality’, the simplest, the least capable of producing its own simulation.

Pursuing this line of thinking, if we are effectively participants in a simulation of the world, and our world is intrinsically a metaverse, that could mean that every one of us, every animal, every plant, every object, has been ‘created’,or, to use the language of computers, ‘instanced’, or that at a minimum the programme’s rules and constants have been programmed. For believers, this creator is obviously God – and this is at the basis of many religions.

This reverie is also potentially fertile for atheists or nihilists : if we are ‘instanced’ beings, we will never totally disappear, something of us is necessarily stored somewhere in the larger universe which is supposed to contain us. Something. Our soul perhaps ?

References :

(1) Jorge Luis Borges, Fictions, 1944

(2) Georges Perec, Species of Spaces, 1974

(3) Published in Philosophical Quarterly (2003) Vol. 53, No. 211, pp. 243-255.