Whether he’s creating art, architecture or video, Daniel Arsham unveils the paradoxical side of general conventions of time and space. The New York-based artist’s boundariless experimentation often brings him to interdisciplinary collaborations, which have become a defining characteristic of his practice. In occasion of his upcoming solo show in Paris titled « The Angle of Repose » at Galerie Perrotin in October, we sent Daniel a blank copy of Exhibition Magazine and asked him to express himself freely as if it was one of common his artistic support. Renowned for installations and sculptures that infuse archeology, history, geology and science with a surreal flavor, Arsham took over the bare template and curated a section of the magazine. We sat down with Daniel to talk about his upcomig projects and explore deeper recurring themes in his work, as well as the inspiration behind his creative intervention on Exhibition Magazine.

Have you ever heard of Exhibition Magazine before? What were your thoughts when you head of this collaborative project and what inspired your creative intervention on the blank copy of Exhibition Magazine?

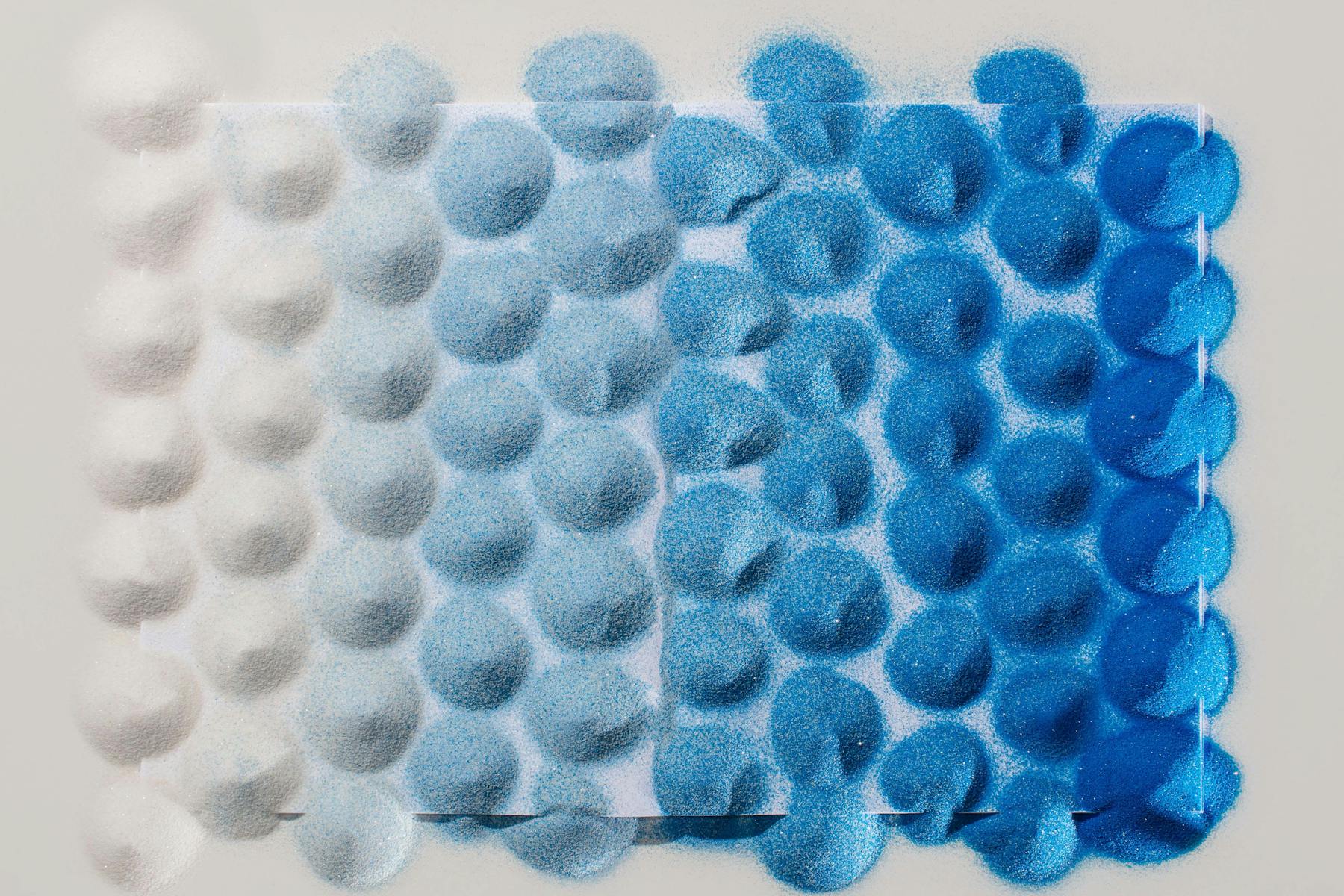

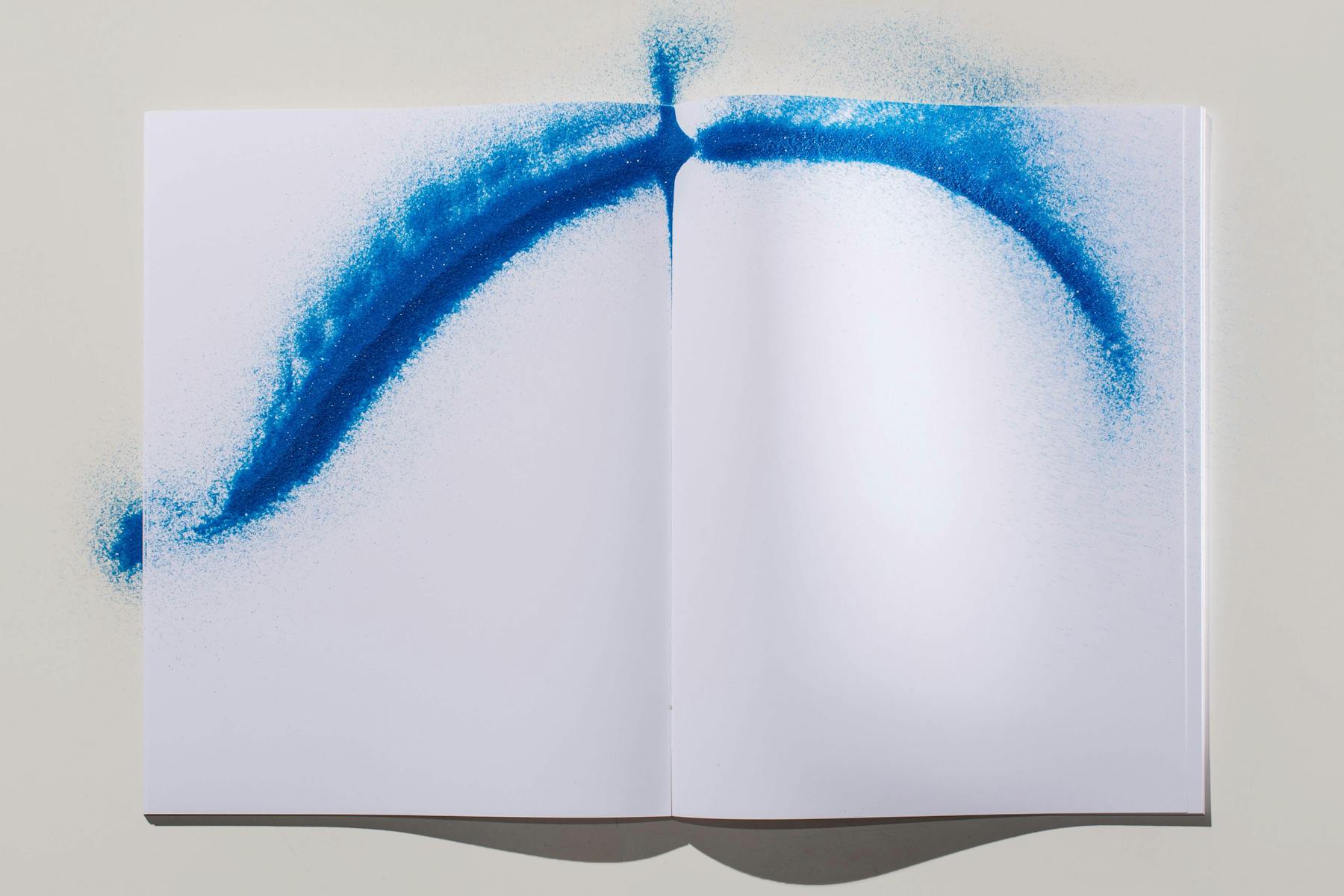

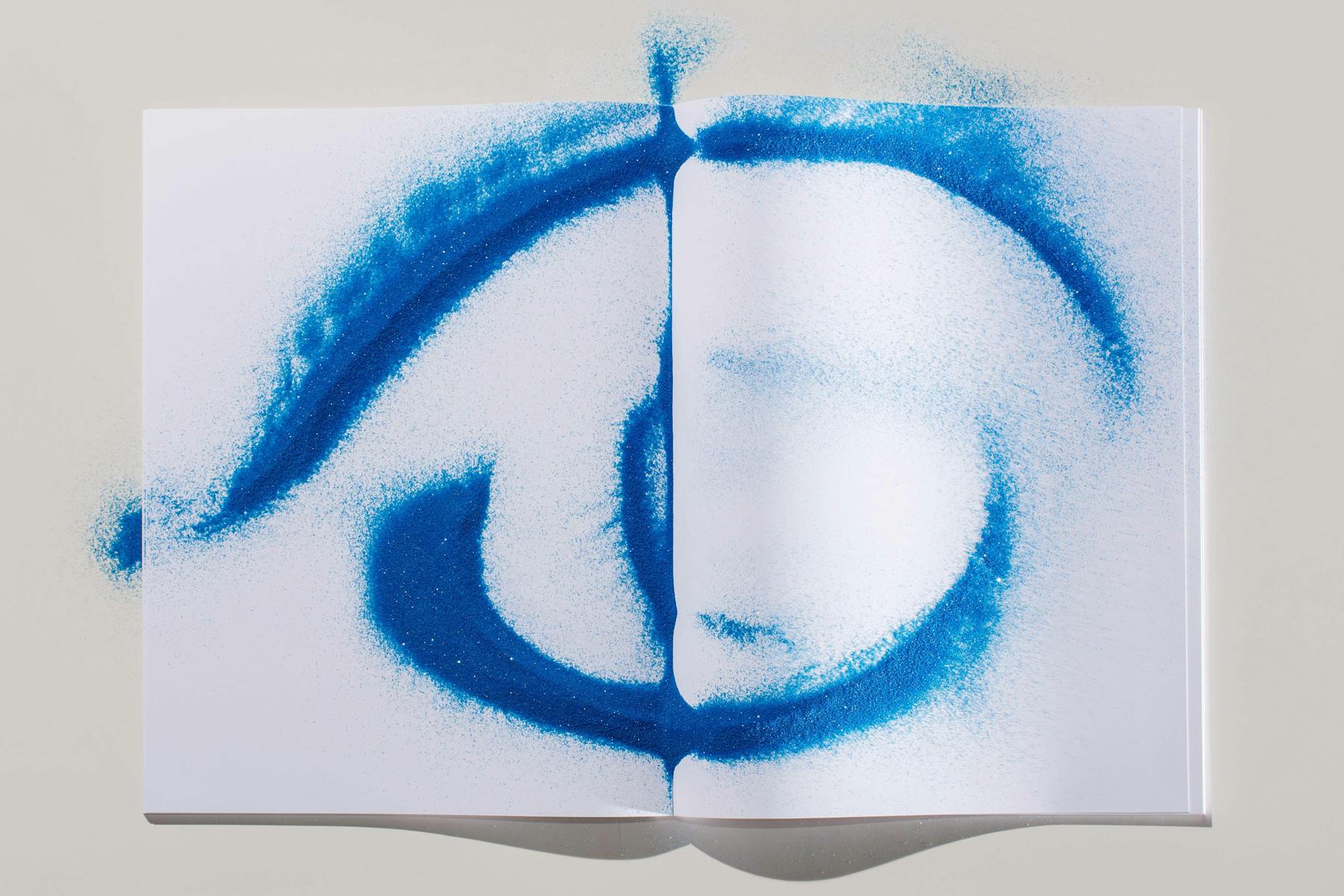

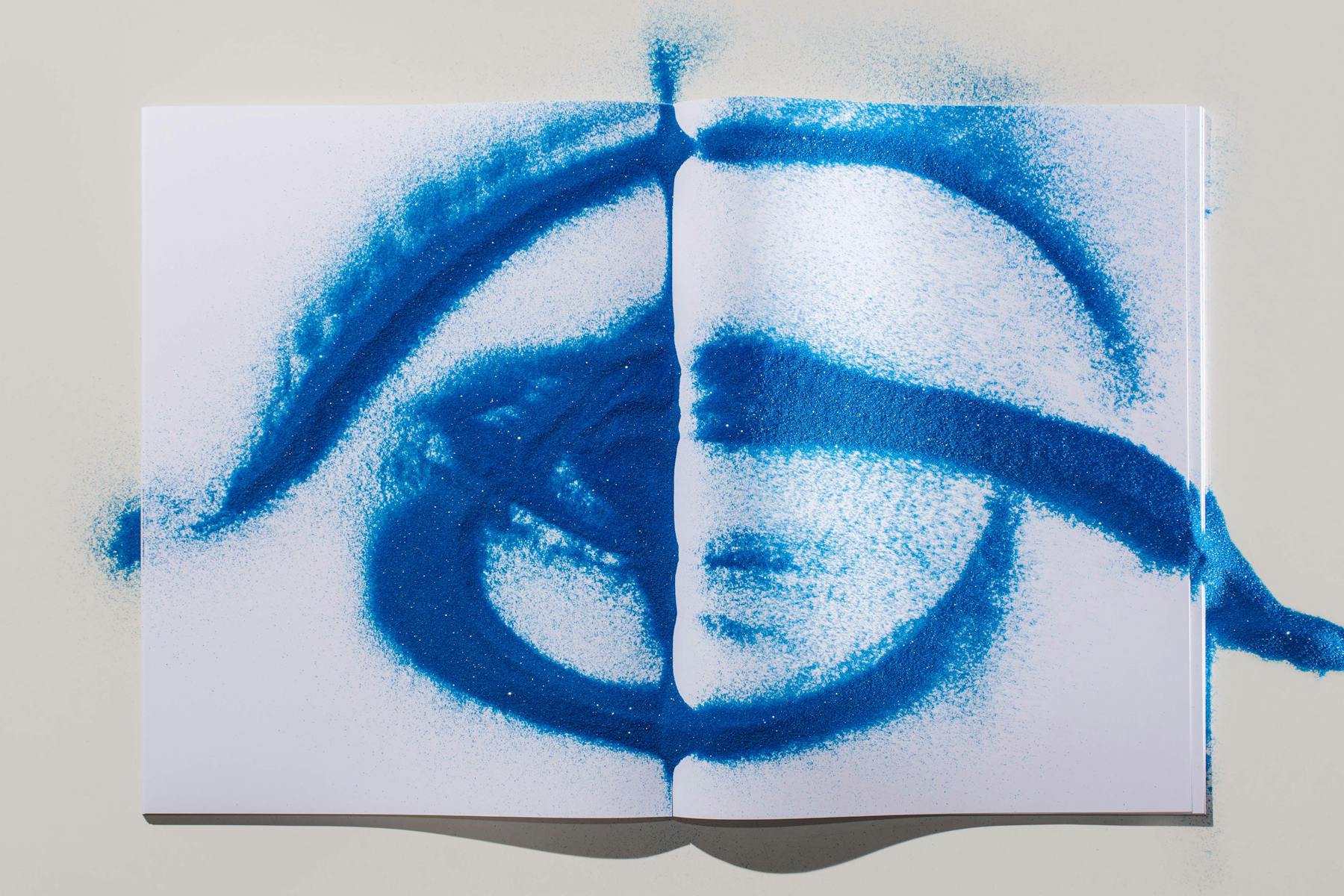

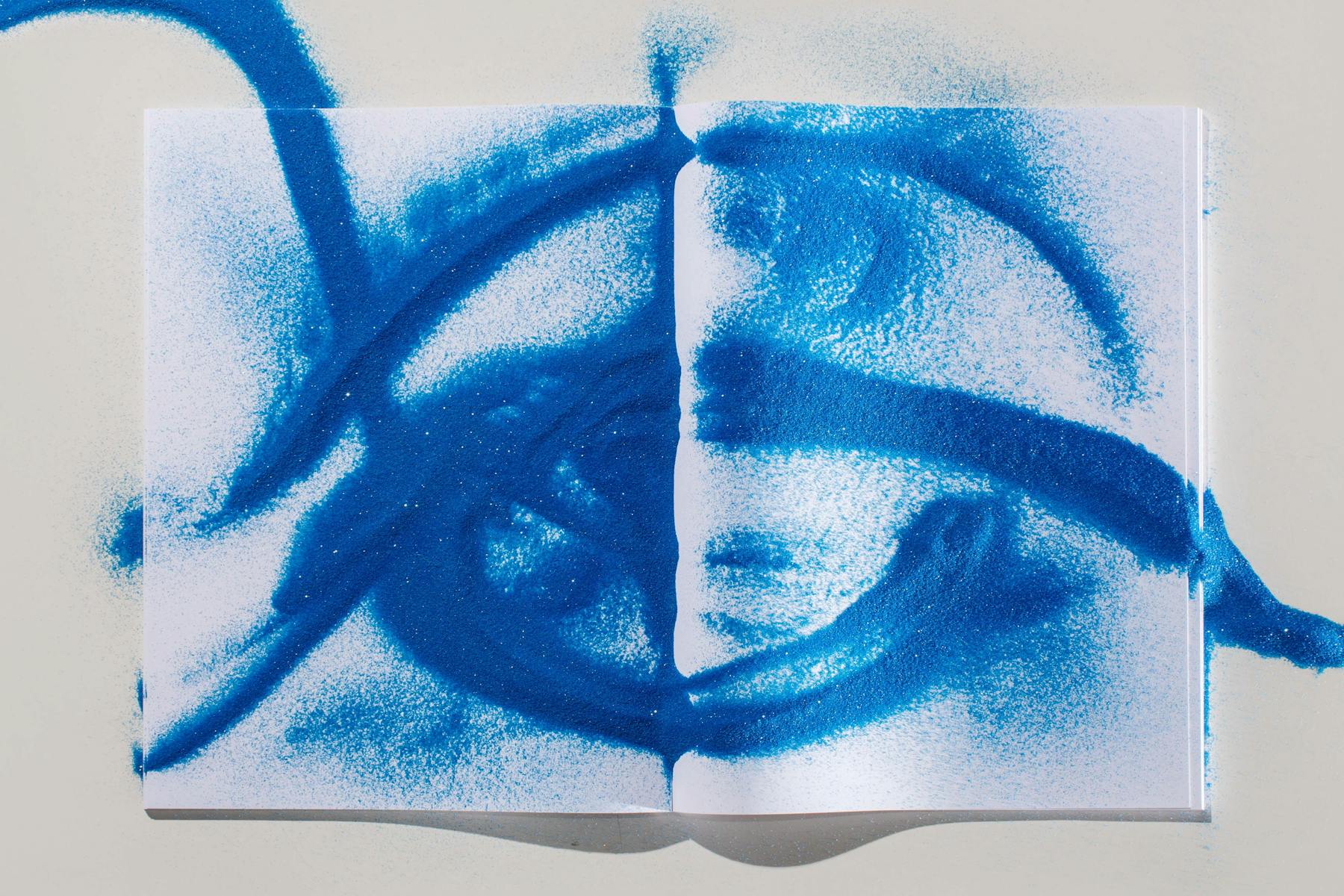

D.A : I haven’t heard about the magazine before, and I find the concept interesting. I like the unusual dimensions of the publication too. I curated editorial content in the past but I have never done an intervention like this before. I am currently working with sand and creating conical piles on flat surfaces. The internal angle between the surface of the pile and the support is known as the “angle of repose” and it refers to the maximum angle at which a material can rest on an inclined plane without sliding down. I am intrigued by its spatial and temporal characteristics, as it suggests an idea of impermanence yet it is still physically present. What I created on the blank copy of the magazine is a series of sand piles in a graduation of color that goes from blue to white, which have been photographed to eventually disappear.

Volcanic ash, obsidian, glacial rock, rose quartz… primal materials are always essential in your art pieces and somehow add another layer of meaning to the works themselves. When and why did you start using sand as a creative medium?

D.A : I have frequently been working with geological materials as they convey a sense of time. Sand is made of rocks and minerals, and it’s a crystal as well. I explore the way those materials bond and react with different elements, they can also be subjected to change at any moment and form something else. Using them gives my pieces an intriguing fleeting quality, which lets the viewers wonder if they are watching something falling apart or taking shape. I began focusing on sand for my exhibition at High Museum of Art in Atlanta, where I recreated a Japanese Zen Garden and several sculptural works featuring hourglasses.

Speaking about hourglasses, the latest short movie you directed is titled “Hourglass”, which echoes the title of your show in Atlanta that opened in March. This object somehow embodies a central theme of your entire artistic production: time. Can you tell us more about your fascination with the hourglass as an object and with the sand that makes it function?

D.A : The hourglass notably measures the passage of time but when you watch it, you have the impression that time stretches and minutes are never ending. There is an element of repetition and ephemerality given by flow of the sand that also relates to Zen Gardens and the repetitive act of raking the sand. Another thing that intrigues me about hourglasses is that the bottom and the top are constantly exchanging, there is not just one sense. According to which way you turn the hourglass, you can see a different sculpture slowly unveiling, like an archeological discovery once hidden in the sand.

Looking at the Zen gardens-inspired work in Atlanta and at the “Circa 2345” show that took place in New York last Fall, one can sense certain lightness, probably given by the colors you recently started to include in your work. Would you say that you are shifting to an artistic phase in which reality is tackled in a more abstract, dream-like, way?

D.A : Not really. A lot of the work I am doing is still in black and white. Colors allow me to highlight the proprieties of materials differently and explore them with a wider spectrum. Even when I use color I always limited my choices according to the materials I am going to use. Monochrome still has many nuances though.

We know you have been colorblind all your life and you recently got some glasses with special lenses that allow you to perceive more shades of colors. Is your world’s vision completely changed?

D.A : I actually wear them only for specific reasons and I mainly use them as a working tool, for example to check the exact color of a pigment. The world in full color somehow gets too busy.

When you look at magazines, do you use the glasses?

D.A : No.

The theme of our current issue is “Midnight”, what kind of connections does it suggest to you?

D.A : I’d say space and planets, and especially the moon. I have been working on a series of Moon Phases sculptures realized in a gradation of blue shades such as the sand piles I created on the magazine. The color blue suggests the glow of the moon and bluish light you see in the sky at night.

In all your works there is a contrast between something that is slowly fading and something that is extremely solid and meant to resist the flow of the years. How do you deal with the notion of impermanence, the past and the future?

D.A : I think a lot of my work is a blend of all these things. For example the concept of the Zen Garden that I explored in the exhibition in Atlanta is something that has existed for hundreds of years and always looks the same, but it’s actually new and recreated every single day. The garden itself stays untouched through time but the patterns in the sand are changed. There is a sort of confusion in between something that conveys an idea of permanence and the actual impermanence of it. I played around and manipulated all these elements as well as the notion of time, not only the one spent in creating and recreating it, but also its historical temporality.

Does the dualism between ephemeral and concrete in your work have something to do with the hurricane you experienced in your childhood and your perception of solidity?

D.A : The hurricane that I was able to witness and seeing the architecture being changed at incredible speed and in a violent manner definitely inspired many of the works that I make, which manipulate architecture. They can convey a similar unsettling and uncanny feeling, yet they also are quiet and subtle. You could enter into a room with one of those works and not notice it immediately. Some of what I do may be an extension of that experience and at the same time a subtle undermining of it.

Would you define your way of “preserving” elements of our culture and history through the Fictional Archeology body of work a form of reaction to the prospect of a “dematerialized” future?

D.A : I wouldn’t say so. I try to choose objects that are iconic and things that a wide group of people from different Countries would be able to recognize and I think the works function in the same way in Europe, in the USA, and Asia. Globalization has created objects that are recognizable and mean the same things to a big and eclectic number of people and I tap into that. None of the works have a specific meaning or purpose; they are more like an invitation to rethink ordinary things and the universe we are used to seeing them within.

From photography to sculpture and architecture you tackled different medias and different tools of creative expression. What pushed you towards the videos and short-movies that you have been directing in the past months?

D.A : Just my curiosity of exploring another medium and the desire to push myself into new areas. Whenever I entered other fields such as architecture, design, or movies, I have always found good partners that assisted me. My approach is very slow, it took me a lot of time before I was comfortable to release any of the film work and to this day I never shown any of my photography publicly, except for few images on my Instagram.

What do you think of paper as support and printed press as a way of convey art and information?

D.A : I do enjoy it. I like books as an object, yet I think print is becoming more of a luxury. It’s nice to have magazines but often you don’t want to carry them around or you forget them. Most of the information that I absorb is from digital devices, but I still buy a lot of books and magazines.